Comparison of 8209 people assessed in management :

The 7 qualities of the best managers and leaders

the 8 differences between men and women among the best managers

the differences in managerial skills according to the level of responsibility held

The qualities of good managers and leaders

CAN WE ALL BECOME MANAGERS OR LEADERS?

- The 7 common personality traits of the best managers and leaders,

- The 8 differences between men and women with the most developed managerial talent,

- Differences in managerial skills according to level of responsibility,

- The 2 key differences between young and more mature managers,

- etc.

Leaders are the best managers!

1. Executives and managers of managers have the best management results!

- Out of the 13 skills assessed by the test, they have the best results on all of them, with the exception of stress management and organising the work of their teams.

- They use delegative management as their primary leadership style, followed by participative management.

- They are also the company’s top salesperson.

- However, of the 561 managers assessed, 90 had a management talent index lower than the average for non-managerial employees… So some of them have room for improvement!

- Men and women had similar results, but showed different personality qualities for the same level of management, including more assertive leadership in the case of men, and greater empathy in the case of women.

2. The qualities of the best managers

- In their intellectual structure, they have developed an ability to synthesise ideas and can project themselves easily into the long term.

- In their energy, they enjoy challenges and have a high work capacity, while managing their stress.

- In their internal and relational structure, they have developed a degree of trust in themselves and others that enables them to be frank in their dealings.

- They are particularly agile (on the 3 agility indicators: situational, intellectual and emotional).

3. Management shapes personality…

- In other words, management is a profession in its own right, requiring personality adjustments to develop real skills. It’s like working on yourself.

- Skills are directly linked to personality, over and above theoretical learning.

- If the changes are significant, the population with low indices of managerial talent shows the weakest evolution of personality. Rigidity is therefore certainly a vector of non-evolution.

The study is developed in more detail below, but here are the first elements we wanted to share as a preamble.

Management study: assumptions and comparative panels

Does the proverb “practice makes perfect” apply to management?

Many companies are giving experienced experts the job of operational manager to oversee the team in which they used to work. It’s a logical and well-founded development. What do the statistics tell us about the potential for people to move into management?

- The results of this major study reveal that the higher the level of managerial responsibility, the more managerial talent is developed – in other words, executives and managers of managers have a higher level of management skills than operational managers or employees with no managerial experience.

- Among the best, we identify 7 qualities of the “good” manager…

- Note: some managers seem to progress faster than others, when the study is refined. It seems that some will always have management difficulties..

- The professional context influences the managerial skills developed. In other words, the corporate culture influences the predominant skills of managers, as well as their leadership styles.

The notion of a “good manager” is a relative one and needs to be analysed systematically in a given context. However, the study carried out here does identify some fairly significant differentiating qualities.

All these elements seem to be based on common sense, but proving them through a complete study is a first, and also reserves some surprises.

PREMISE: WE CAN CHANGE AND IMPROVE OURSELVES

The research work that went into creating the Assess Manager management test is based on the premise that “anyone can change, at any age”, refuting the idea that people are locked in or that their personality is fixed. On the strength of this optimism, we decided to measure it concretely so as not to influence the results and to verify this postulate.

Plan of the study results (rapid access)

- Personalities evolve, nothing is set in stone!

- Comparative panels of the study and evaluation method

- The personality of ‘good managers

- The skills of “good managers

1. Temperament versus personality

Many psychologists refute the idea of the evolution of personality, and propose or use personality tests that measure temperament rather than personality and the influence of context on personality. Context can reveal a person’s full potential or, on the contrary, hold it back. Temperament is, in a way, the basis on which we are born, and context shapes our basis. Context includes our parents’ upbringing, what we learn at school, the impact of the country’s culture, professional interactions, etc.

2. The impact of working life on personality

This study shows us that our personality, which is shaped over the years, is also impacted by our professional experience. What’s more, when a person is a manager, their personality seems to evolve more than that of an employee with no managerial responsibilities. The greater the level of responsibility, the more the personality seems to evolve. That’s the first thing this study shows.

3. The development of managerial skills is proportional to the level of responsibility

Secondly, it also shows that the managerial skills measured in 5 distinct populations with different levels of responsibility are proportional to their level of responsibility. In other words, an executive develops more management skills than an operational manager. Similarly, an operational manager develops more management skills than an employee with no managerial responsibilities.

Executives and managers of managers have a fairly similar skills curve. Employees with no managerial responsibilities (‘non-managers’) have developed the fewest skills, their results curve being the most central. The differences are fairly small, given that we are talking about population averages, and we present the study panels below.

While these conclusions seem logical, they enable us to identify two key points:

- Experience shapes personality

- Experience develops competence

Two questions emerge from this:

- Can anyone really become a manager or director?

- Should talent identification be carried out several times in a career?

When we analyse the groups of managers in more detail, it becomes clear that while some people progress a great deal, others do not. The averages show the changes, but some sections of the population are the exception rather than the rule.

FROM MANAGER TO EMPLOYEE: COMPARATIVE PANELS IN THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY

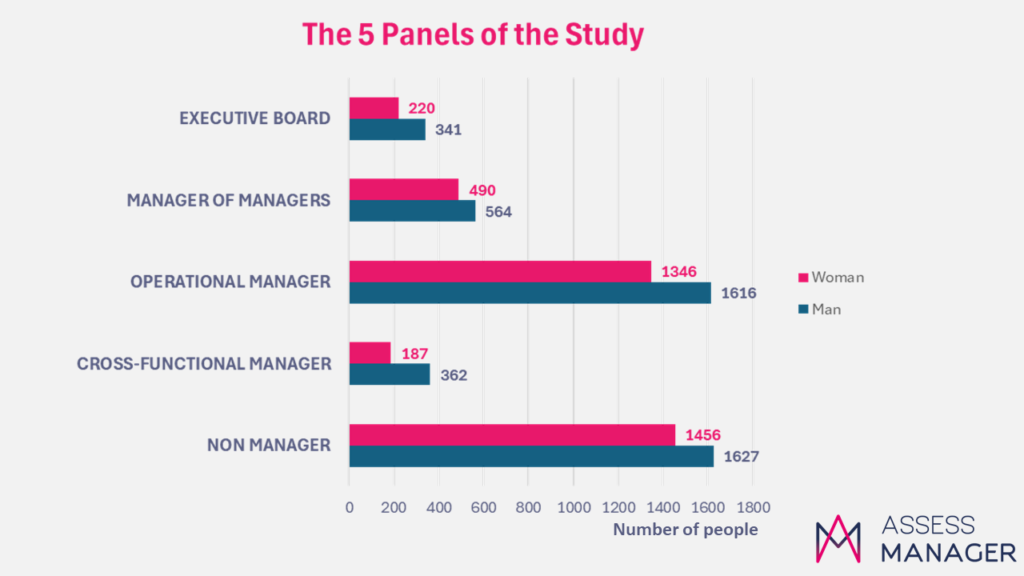

Figure 2 – 5 Panels in the comparative study of managerial skills .

The proposed study brings together the analysis of 8209 people whose declared function is clearly identified and validated, as well as their age, sector of activity and gender.

The distribution of men and women is fairly balanced here, with 45% women and 55% men, which is representative of the working population in France in 2020 and declared to be in professional activity: i.e. 46.6% of women in activity according to INSEE indices (Source INSEE, 2020 figures: 14,176,000 women, with an activity rate of 68.2%, and 14,869,000 men with an activity rate of 74.7%)

Men and women: differences in responsibilities

While the distribution of men and women is fairly linear for all groups, cross-functional managers and senior executives are exceptions to this rule, with men holding 61% and 66% of these positions respectively.

Executives versus operational managers: emblematic ages

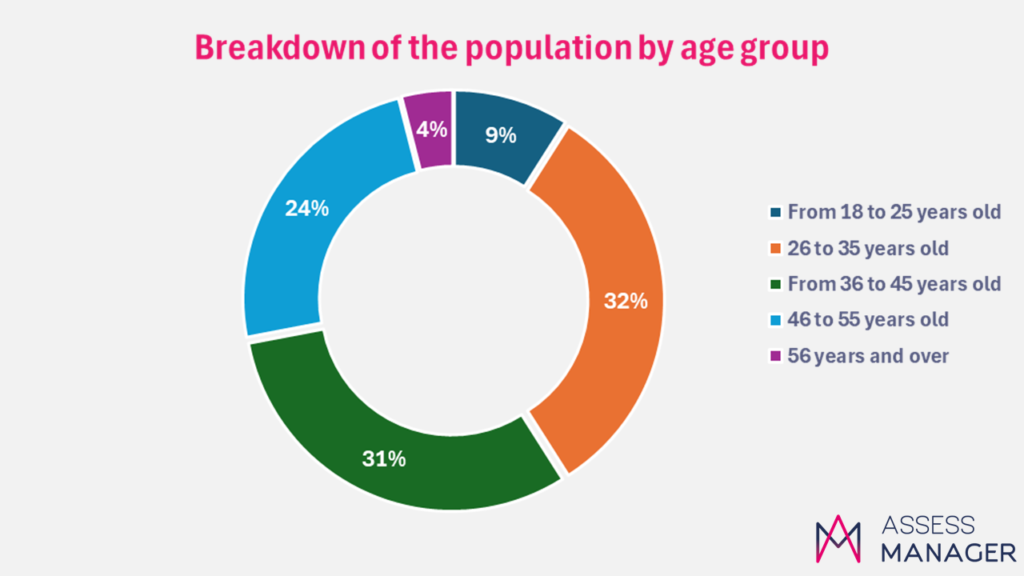

Figure 3 – Age distribution of the population studied.

A closer analysis of these 2 graphs shows that 75% of executives are aged between 36 and 55, while 66% of operational managers are predominantly younger, aged between 26 and 45.

In other words, it would seem thata person who aspires to managerial responsibilities is more likely to achieve his or her goal before the age of 45. You don’t have to wait until you have 25 years’ professional experience to become a company boss. However, experience certainly helps. The funds required to launch a business may also explain this trend.

The service sector is dominant

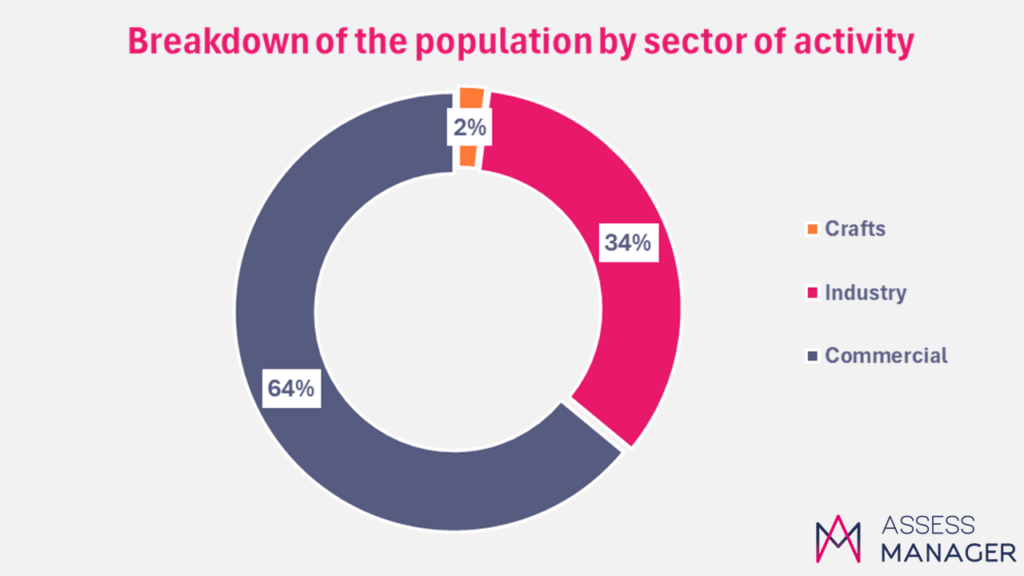

Figure 4 – Breakdown of the sectors of activity of the population studied.

We complete this analysis by looking at the distribution of sectors of activity: the majority of the population is represented in the tertiary sector (64%), compared with 34% in industry. Craft trades are poorly represented, with only 2% of the population tested.

This is not representative of the distribution of the working population, which is 75.9% in the tertiary sector and only 13.8% in industry. It should be noted that the agricultural sector is not represented in this study, as there are very few spontaneous respondents on managerial evaluation.

Tools used to carry out this study

Methods and tools

- The Assess Manager management test is designed to assess respondents’ management skills and forms of leadership. It consists of 110 questions and situations completed in an average of 23 minutes.

- All the questions and situations are accessible to everyone and do not value the respondent’s position.

- Examples of situations proposed in this test: your reactions to failure, to a car accident, to a new time-consuming work method, your reading preferences when discovering a magazine, etc.

In this way, we begin by establishing a personality profile for the respondent, based on their natural temperament on the one hand, and the personality changes they have implemented as a result, in particular, of their professional experience. An innovative algorithm is then used to establish the respondent’s managerial profile, whether or not they are in a managerial position at the time they answer the questionnaire and the situations proposed.

It is therefore a predictive tool for determining a person’s managerial talent, using personality indicators that are much more developed than a traditional personality test to draw up an exhaustive managerial profile. A number of theoretical frameworks are used to map out personality elements, including neuroscience and the HBDI framework, certain BIG-5 and MBTI indicators,transactional analysis, neuro-linguistic programming and Karpman’s dramatic triangle.

The test was developed over a period of 5 years, including 2 years dedicated to scientific validation. This was a particularly long time, because there was no recognised management test on the market that could be used as a scientific skills benchmark, particularly in terms of construct validity.

The theoretical management benchmarks measured in the Assess Manager test are set out and illustrated in 2 management reference books , “Le management à porter demain”, written by the founder of Assess Manager, Virginie Loisel and published by EMS Coach.

This study is therefore based on the answers given by 8209 people, who have been divided into 5 panels to analyse the differences in the participants’ managerial skills, their managerial agility and their leadership style.

The personality of good managers

1. Personality differences between a manager and an employee

- Managers are above all forward-looking strategists and communicators. The organisational aspect, which underpins the search for a framework and security, is not a driving force in their work. They have a more developed sense of challenge than other populations.

- Employees without managerial responsibility are more dominated by emotions and need to be reassured.

- Managers, by occupying their position, strengthen their strategic side and their expertise, more than all other populations. Managers of managers show a similar but less marked trend.

- While communication was the main focus for executives, their role teaches them to manage their emotions and reduce their communication to adopt a more adjusted style, as each of their words can have a relatively significant impact on employees.

2. Common or distinctive components of top management talent

The 7 common personality traits of the best managers and leaders

A management talent indicator is calculated to differentiate between populations. This indicator is valued mainly on the basis of managerial skills, managerial posture and agility.

As the leaders with the best management scores, the personality traits of the best leaders are also the personality traits of the best managers:

- In their intellectual structure, they have developed an ability to synthesise and project.

- In terms of energy, they enjoy challenges and have a high work capacity, while managing stress.

- In their internal and relational structure, they have developed confidence in themselves and in others, enabling them to be frank in their dealings.

- He is particularly agile.

Other traits stand out. Those listed here are significantly superior to other managers whose managerial talent was inferior.

Differences between men and women with the highest managerial talent

By isolating the managers with the highest level of managerial talent (same levels for both groups), we compared the significant personality differences between the male and female populations. Differences of more than 5 points on panels with highly averaged results are considered significant.

- Men position themselves more as leaders and have a greater appetite for challenges.

- Men’s stress levels are higher than women’s, but the effects are more stimulating for men than for women.

- Women take more initiative.

- Women question themselves more easily and are more motivated by their personal development and the learning generated through their work than by social recognition, to which men are more sensitive.

- Women are more empathetic than men and are more able to imagine the feelings of those they work with.

Personality differences between managers according to sector of activity or age

SERVICE SECTOR VERSUS INDUSTRIAL SECTOR

We have isolated the managers with the highest level of talent by business sector in order to identify the personality traits that potentially differentiate the 2 sectors.

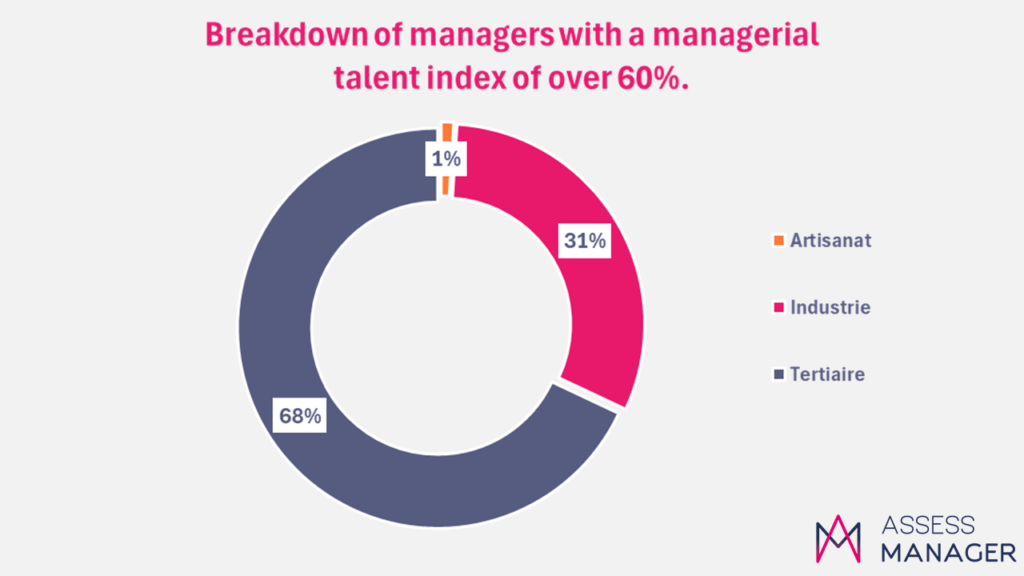

Figure 5 – Distribution of managers by business sector with a managerial talent index above 60%.

3 elements stand out significantly:

- Service sector managers have a more global view of business situations.

- They are more creative.

- Managers in industry are firmer in their stance and respond more readily in the negative when approached.

Managers with the highest index of managerial talent are more represented in the service sector. However, their representativeness remains fairly parallel to the distribution of the working population in the panels studied

YOUNG MANAGERS AND EXPERIENCED MANAGERS

We isolated the managers with the highest level of talent by comparing the 26-35 age group with the 45+ age group.

2 elements stand out: younger managers are perhaps more “spirited”

- They take more initiative.

- They have a greater sense of challenge.

These elements are the result of group averages and highlight only characteristic elements of major trends and are not, in fact, exhaustive.

3. Profile of managers and managers of managers

Looking at the results of the personality and management test on the populations of executives and managers of managers, we can see a number of elements:

- Qualities of a good manager: Executives have better management results on average than all other managerial populations. Managers of managers have very similar results to executives in terms of managerial performance.

- Company directors show marked trends in their personality qualities, with a greater predominance of strategist and communicator profiles than in the case of the other populations studied.

A comparison of the degree of change in the personalities of the populations shows that managers are the people who have changed the most. Being an executive or a manager with a high level of responsibility involves a great deal of learning. Management is one of the professional activities that takes you out of your comfort zone. It is not a science that works by repeating patterns. What works with one employee will not necessarily work with another.

In fact, managers of managers and executives are the two populations out of the 5 panels studied that have the greatest statistical degree of personality evolution (highest indicators of dispersion).

The higher the managers’ managerial talent index, the higher their personality evolution index.

If we take this study a step further and select managers with a managerial talent index of over 60%, and compare them with the panel of employees with no managerial responsibilities, the difference in dispersion between the 2 populations is significant:

- employees with no managerial responsibility show an index of change of 4.7% (index of dispersion on personality changes at the level of HBDI indicators), the lowest of all the populations studied.

- In comparison, executives with more than 60% managerial talent have an evolution index of 11.4%.

- Managers with a managerial talent index of less than 60% have a personality development index of 7.4%.

The managerial function is more important than other functions in the companyfor the development of an individual’s personality

In conclusion, the qualities of good managers: WHILE MANAGEMENT SEEMS MORE FAVOURABLE WITH CERTAIN TYPOLOGIES OF TEMPERAMENT, THE DEVELOPMENT OF MANAGEMENT SKILLS IS PROMOTED BY PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT DIRECTLY RELATED TO AGILITY.

Management is a science combining dynamic psychology and agility, development theories, performance techniques and tools. As such, it is acquired over and above any predisposition or intrinsic qualities, even if some profiles have an innate predisposition that is much more marked than others.

So there are certain innate predispositions for becoming a manager, but learning by doing can fill what might at first appear to be a gap, all the more so for people with a certain malleability for learning and an openness to change.

4. Do you have to be a good manager to be a company director?

Of the 561 managers assessed, 16%, or 90 managers in total, had a management talent index below 40%.

For the level of responsibility and stakes involved in running a company, a 40% index of managerial talent is a priori too low to be sustainable. The expectation for this level of responsibility is rather 20 points higher according to the metrics of the Assess Manager management test.

This study does not link the managerial skills of executives to the economic performance of companies. It would therefore be worth extending it by making this precise correlation in order to reach scientific conclusions. If managers of managers seem to achieve a level of management almost equivalent to that of executives, it is conceivable that the former can make up for the shortcomings of the latter.

In any case, some sectors are certainly more competitive than others, and require a higher level of performance to achieve positive economic results.

- In the craft sector, 1/3 of the managers assessed had a management performance of less than 40%.

- In industry and the service sector, this applies to only one manager in 6, i.e. twice as few as in the craft sector.

Can we conclude from this that the more competitive the market, with supply outstripping demand, the better the management performance, and vice versa?

In conclusion, it still seems possible to be an executive with limited managerial talent, particularly in sectors where supply is lower than demand. In this case, there will certainly be a high turnover in these companies and significant potential for optimising profitability. There may also be opportunities for company takeovers..

In competitive sectors, it seems that management has become a key factor in company performance, with managers with low managerial skills being less well represented.

managerial skills according to responsibilities

Managerial talent and managerial agility

WHAT ARE THE DOMINANT DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE 5 PANELS IN TERMS OF AGILITY?

Managers have the best results in terms of agility in the 3 areas assessed: emotional, intellectual and situational agility. It should be noted that cross-functional managers also score highly in terms of emotional agility.

Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence means moving from a state where emotion is the boss to a state where emotion is a resource.

Figure 6 – Differences in the level of emotional agility according to the level of managerial responsibility held

Emotions send out a message, and I know how to listen to them, make them aware, and take appropriate, adjusted action if and when the time is right. I’ve also developed a certain amount of empathy, so I can detect the emotions at play in the person I’m dealing with and help them to deal with them in an appropriate way. If I’m scared, the emotion tells me to “be careful”. I can listen to it to make a decision more secure, and identify whether it is justified, over and above any natural tendency I may have to develop fears when making decisions, for example.

Cross-functional and executive managers have the most developed emotional agility of the comparative panels measured.

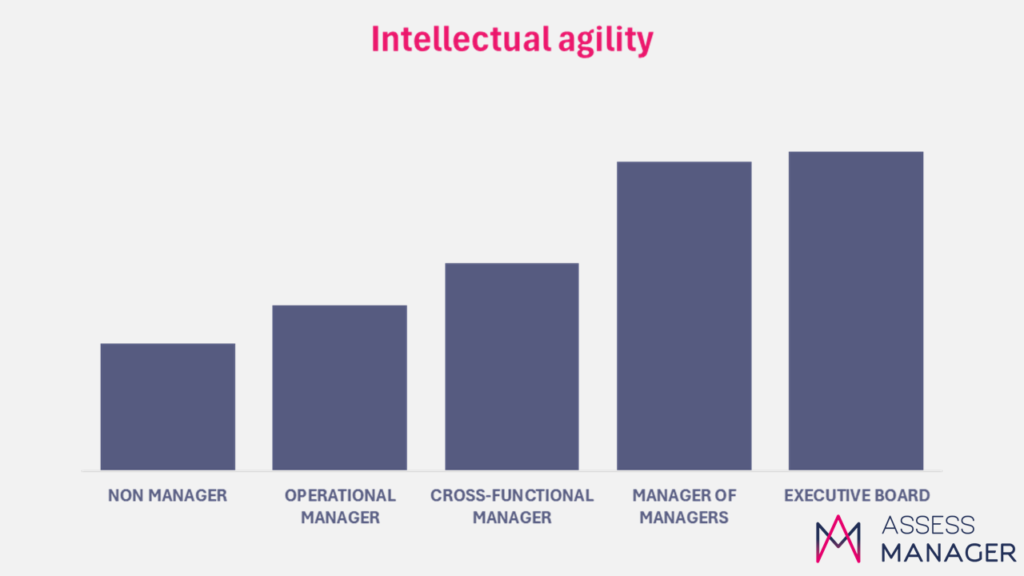

Intellectual agility

Intellectual agility is a form of intellectual empathy towards others.

Figure 7 – Differences in the level of intellectual agility according to level of responsibility

It is associated in part with an individual’s intellectual capacities and also with his or her pedagogical skills in adapting his or her mode of reasoning to that of the person with whom he or she is dealing and thus delivering explanations that make the message comprehensible to the person with whom he or she is dealing.

Here too, neuronal plasticity is important. And contrary to the beliefs of the past, the brain is an extensible organ that is not determined by age unless it is affected by specific diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

The higher the level of managerial responsibility, the higher the level of intellectual agility measured on comparative panels.

Situational agility

Situational agility is tenuous, but the management styles used by managers are differently distributed.

Situational agility is defined by the ability to use diversified management styles adapted to the situations and people involved.

The results are very mixed between the 5 panels of managers. On the other hand, the distribution of management styles is quite distinct according to the level of management occupied.

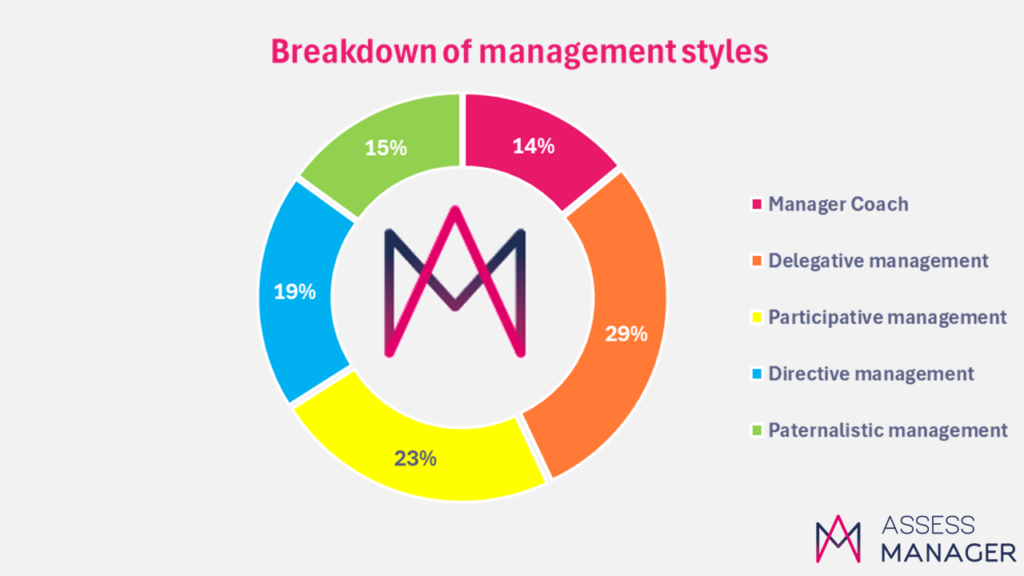

The panels of CEOs and managers of managers assessed in this major study reveal results with very similar management styles. To avoid redundancy without added value, we show here the results for executives, which are similar to those for managers of managers:

Figure 8 – Management styles potentially used by CEOs

Delegative management is in first place for these 2 populations of managers, who set the course and entrust the teams with the role of implementation. Participative management, which has been in vogue since the 1980s, comes in 2nd place, but would not work without the ability at certain times to make decisions and reassure people that there is a “pilot in the plane”(authoritarian management).

Executives and managers of managers take on the role of giving responsibility, bringing people together and making decisions.

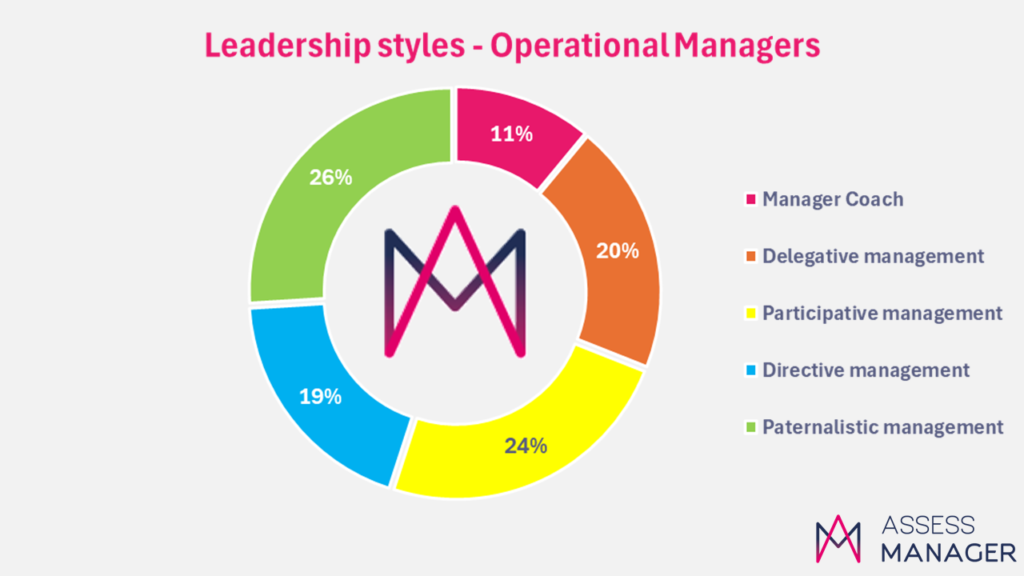

The results of the panel of operational managers are quite different:

Figure 9 – Management styles potentially used by line managers

Paternalistic management is now more in the background, aimed at people who normally have sufficient skills not to be infantilised or reassured. The paternalistic manager takes his employees by the hand. Logically enough, this is more common in the other populations represented, such as operational managers (opposite).

The manager-coach is a posture evaluated as an overlay to the other management styles in the Assess Manager test; it is capped at 20%. This means that managers use 14 of the 20 points available to help their teams grow and find their own answers.

Although directive management is not very popular in the collective unconscious because of its authoritarian connotations, all the manager panels use this management style to implement decisions and move projects forward. Directive management is used in emergency or sensitive situations: firefighters and hospital doctors in particular will use it more predominantly, as the stakes can be very critical. The economic world and the recent health crisis have developed the reactivity of directors and managers of managers, which seems to be useful in such a context. As long as participative management is also represented, the balance seems relatively positive. For the record, the panels were taken from Assess Manager management tests carried out during the health crisis, i.e. in 2021.

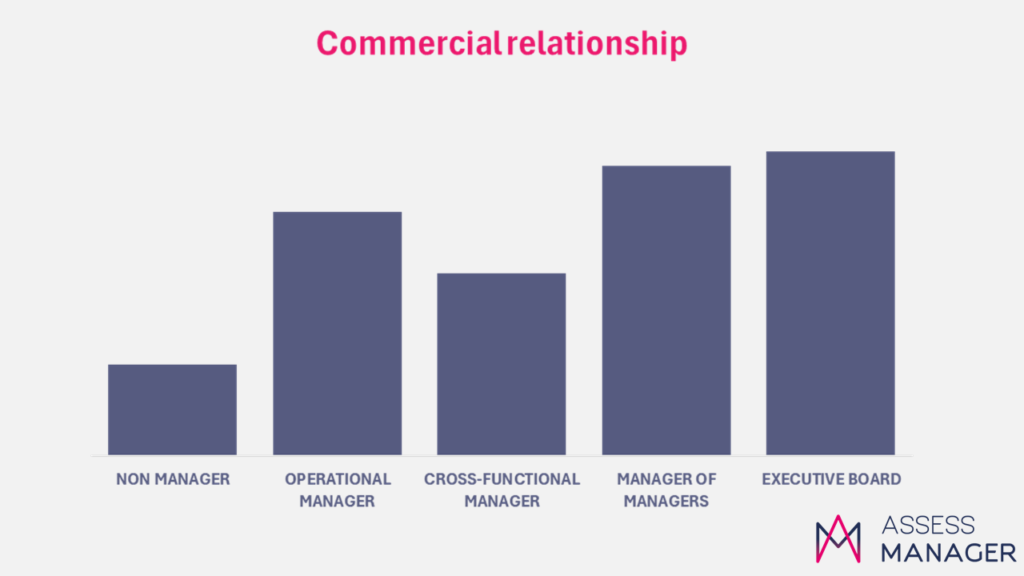

Managerial and commercial talent

Isn’t the manager the company’s most important salesperson?

Figure 10 – Commercial sensitivity of different managerial populations – Managerial qualities

This indicator is assessed in the management test but not shown in the reports. The results were not certain enough to be used. They have been under observation for 3 years. Here are the graphical results of the distribution of the commercial sensitivity indicator for the different panels.

We might have expected ‘non-managerial’ employees to be more oriented towards customer relations, as they are often the front-line interface. However, the panel is represented by a very diverse population, some of whom have no contact whatsoever with customers (accountants, laboratory technicians, etc.). The results for non-managers should be looked at in more detail by separating the sales functions from the more administrative functions.

Cross-functional managers sometimes include quality or process functions that have a history of standards that are sometimes at odds with the quality of customer relations, even though standards have now largely put the customer back at the heart of thinking and methods. The results should evolve over the coming years, bringing greater flexibility and common sense.

The graph shows that executives and managers of managers have more developed commercial qualities, followed by operational managers, who occupy third place out of the 5 panels studied.

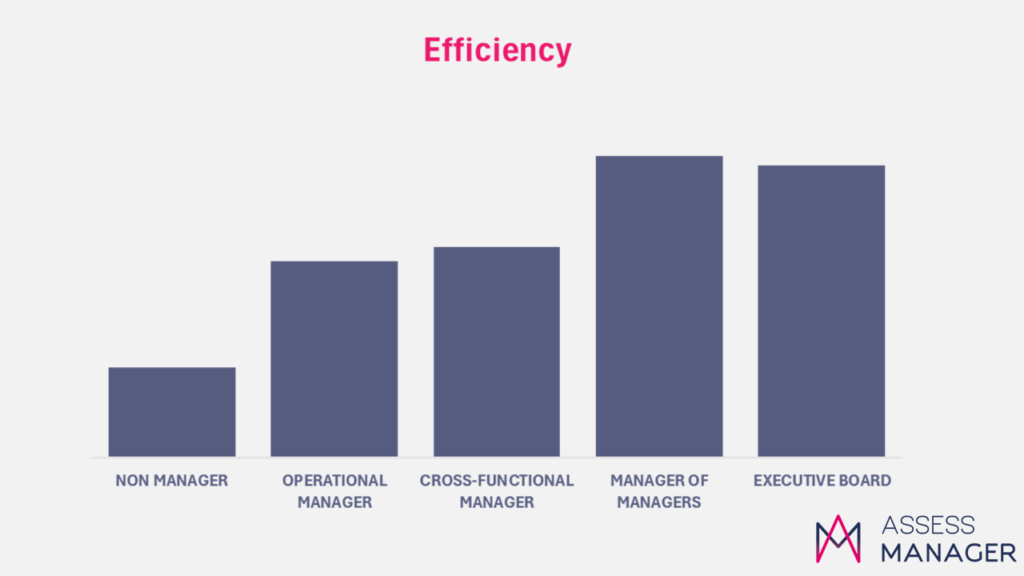

Managerial talent and efficiency

In terms of efficiency, it is the managers of managers who seem to win the day, with the highest level of skills of the 5 panels represented (including 4 panels of managers)

Figure 11 – Comparative efficiency of the 5 panels

Managers of managers have qualities of anticipation when it comes to organising work, which favours this slight difference compared to executives.

Operational managers are often caught up in the day-to-day flow of work, which can cause them to lose sight of priorities or spend less time managing optimisation. It is the support of cross-functional managers that can encourage this optimisation.

In addition, managers and managers of managers have a wide range of subjects to deal with, which means that they can work with an ability to stand back and synthesise, thereby promoting efficiency. On the other hand, operational managers and non-managerial employees are more likely to be in charge of 0 defects, keeping an eye on the smallest details, which are a major source of wasted time – cf “looking for a needle in a haystack”.

The most highly-developed managerial skills – comparing the executive with the operational manager

What are the most highly developed managerial skills between operational managers and executives?

There is a certain consistency in the managerial maturity of executives across all skills, compared with other managerial groups. The 13 skills assessed in the managerial skills reference framework are presented as follows:

Set of graphs – Figure 12 – The 13 managerial skills by level of managerial responsibility

You can take the management test used for this major R&D study and obtain your complete managerial profile: managerial posture, leadership and skills

Managerial skills: Linearity of results and logical exceptions

While these 13 skills show fairly linear results in terms of skill levels by managerial group, with a general predominance of a higher level achieved by executives and managers of managers, there are some interesting and logical exceptions.

Firstly, the skill of ‘organising and planning the work of teams’:

If we look in detail at the sub-skills, we can see that the groups of managers of managers and cross-functional managers are more involved in anticipation, whereas those who perform best on the sub-skill of organising the details of a project to achieve results are operational managers, followed by cross-functional managers.

Then there is the skill of ‘managing conflict’:

We can see that cross-functional managers are at a higher level than managers of managers. In fact, cross-functional management is often a delicate position, involving teams without a hierarchical role. As a result, this population has certainly developed a particular skill for getting teams on board and managing tensions.

This logic is certainly reflected in the skill of “managing team stress”.

In the “Manage team stress” skill, the first sub-skill is dedicated to managing one’s own stress, while the second is dedicated to protecting others from one’s own stress.

Cross-functional managers have developed a particular skill in this area. How can you get employees to participate actively if they are a source of stress? Intrinsically, they can have this effect by providing extra work. So there could be a direct link between conflict management and the generation of stress in companies. Apart from the organisational component, which can generate stress, could we imagine that the greatest source of stress in the company is at the relational level? The connection between these two graphs allows us to question this connection.

While executives and managers of managers have the highest scores for managing their own stress, they have the lowest scores for their ability to protect others from their own stress. This suggests that one way of managing stress is to pass it on to others. Non-managerial employees have the lowest scores on their ability to manage their own stress.

Delegation:

Lastly, we may be surprised to find that delegation skills are intrinsically at their highest for executives and managers of managers, since they are the ones who make the most decisions and pass on the operational implementation of decisions.

In terms of delegation skills, while executives and managers of managers come out on top, the sub-skill of monitoring and controlling delegation is mastered more by line and cross-functional managers, who are the guarantors of the proper conduct of operations and the achievement of results.

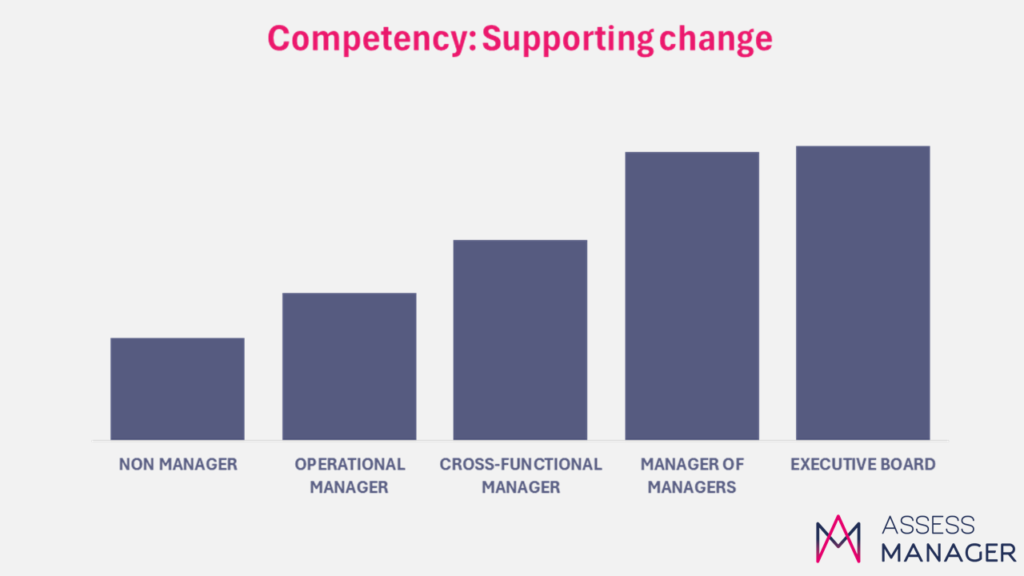

Change, stress and agility:

The skill of “supporting change” is measured via 3 sub-skills, the first of which is “encouraging change”. Executives and managers of managers have a very high score compared to the other populations (more than 11 points difference between executives and non-managerial employees). It could be that change is a second major source of stress for the non-managerial population: their agility being the lowest in terms of emotional, intellectual and situational agility, we understand that their ability to experience learning is a potential source of stress, as change takes them out of their comfort zone.

What can be learned from these initial lessons?

- Bringing about change within the company develops the flexibility andagility of individuals, which are vectors for progress. By stepping out of their comfort zone, individuals put themselves in learning mode. The more they renew their experience, the more agile they become.

- However, some people have a real rigidity when it comes to learning new things, and will reveal themselves more through the development of a certain form of expertise (technical, organisational, etc.).

- Detecting talent only once in an individual’s career is a great pity, given that the index of managerial talent also evolves with experience.

- Finally, while management may be fairly intuitive for some people, it can be learned in any case and develops with experience. Training and coaching certainly accelerate skills.

We would like to correlate the management talent indices of executives with the growth rates of companies, but unfortunately we have not done so and cannot therefore conclude on a parallel between these 2 elements. This may be the subject of a future R&D project within Assess Manager.

Take the management test or equip your company with the management test (no obligation).

R&D MANAGEMENT STUDY SUMMARY

- This study was carried out by Assess Manager on the basis of 8209 people evaluated in management.

- The management test is based on skills illustrated with examples and tools in these 2 complete books.

- Management is a profession, and skills are acquired through experience and the help of trainers and/or coaches. Not everyone is born with it.

- MyCampus Management: Individual and group diagnosis and recommendations for priority training courses

To go further with Assess Manager